Introduction

The question of whether Jacque Fresco’s ideas — especially his circular-city concept — can actually be realized remains relevant today. The vision of a technologically advanced and socially organized “city of the future” still draws the attention of those familiar with his books, lectures, and documentaries. At first glance, Fresco’s whole idea was to build a city founded on science, technology, and — most importantly — new human values.

Are the buildings Fresco showed even possible to construct? Could such a city really be built in months, not years? How would decision-making work there? Is there even demand for such cities, and could this idea of a “city of the future” become reality anytime soon?

In this article, I’ll look at the question of building the first “university city” from both a practical and scientific perspective.

Background

Since founding The Venus Project, Jacque Fresco never stopped developing the concept of the first “university city.” He understood better than anyone that modern cities — many of which were designed hundreds or even thousands of years ago — can hardly be adapted to the real needs of people in the 21st century without sacrificing comfort or damaging the environment.

It’s impossible to rebuild human civilization on a scientific foundation just by planting a few rooftop gardens on skyscrapers. Jacque believed that what humanity really needs is a completely new kind of urban environment — a holistic, self-contained system designed to harness the full potential of technological progress.

In his vision, the future would consist of such cities spreading across the planet, eventually replacing today’s chaotic, polluted, and dangerous megacities. Most people don’t even realize how harmful modern urban environments are — from the constant risk of traffic accidents to the toxic effects of smog, noise, and stress on human health.

Buildings of Unusual Shapes

Jacque Fresco didn’t choose dome-shaped structures by accident. He was primarily interested in their efficiency compared to traditional buildings — and he turned out to be right. Numerous scientific studies confirm the advantages of rounded designs: they show exceptional resistance to hurricanes, tornadoes, and earthquakes, even when the walls are relatively thin.

Domed roofs help regulate interior temperature more effectively in regions with extreme climate variations. A dome with ventilation openings can significantly reduce annual energy use for heating and cooling compared to flat or sloped roofs.

In addition, building domed structures requires fewer materials, and the resulting constructions are far more resistant to decay, fire, and pests — making them both economical and durable solutions for sustainable architecture.

What impressed me most were the numbers: up to 52% less energy use for cooling and 24% less for lighting.

Of course, this doesn’t mean dome houses are a universal solution. Fresco himself never suggested building only domes — among his designs are also semi-cylindrical and modular buildings. Still, such shapes can be seen as the next step in architectural evolution — a step humanity has already begun to take. According to forecasts, by 2030, in just about five years, the market for such homes is expected to nearly double.

They’re not mainstream yet, but they’re steadily gaining popularity — especially in the tourism industry and among people passionate about eco-friendly living, particularly in Europe.

Moreover, modern construction technology has advanced to the point where we can now build structures of almost any shape or complexity. Not all of them are efficient or rational, of course, but from an engineering standpoint, the concepts Fresco proposed are far from the most difficult things we’re already capable of building.

Fast construction of houses.

“Alright,” you might say, “we can build — but how fast? Won’t the city of the future just turn into an endless construction site that lasts for decades?”

Honestly — yes, it will, if we keep relying on outdated technologies and thinking within the limits of old systems.

But if we move beyond traditional methods and let go of familiar habits, it turns out there are plenty of technologies that can speed up construction by tens or even hundreds of times.

For example, a team at MIT led by Neri Oxman developed a mobile 3D printer — a robot on a foldable chassis with two manipulators capable of “printing” structural components ready to be filled with concrete afterward.

In the experiment, such a robot built a dome 15 meters in diameter and 3.7 meters high in less than 14 hours. The thickness and shape of the walls are programmed: for example, the windward side can be made thicker and better insulated, while ledges and curves are integrated directly into the printed structure. According to Neri Oxman, technologies like this already make it possible to literally “grow buildings like living organisms,” combining structure and finish in a single process. These methods drastically reduce both construction time and costs, paving the way for a completely new level of architecture.

With multi-story buildings, things are even simpler. Why? Because they can be preassembled — in a factory, from ready-made modules. Modular construction isn’t a new idea, but in my opinion, it’s often overlooked. Yet it has already proven its efficiency: the Chinese company Broad Group (Holon) built a 26-story residential building of about 4,500 square meters in just five days. And a year earlier, using the same technology, they assembled an 11-story building in only 28 hours.

After assembly, the building is connected to utilities — and it’s practically ready for use. The structure comes almost fully equipped: with elevators, staircases, insulation, and windows. According to the company, these buildings are earthquake-resistant, designed to last over a thousand years, and can reduce air conditioning costs by up to 90% thanks to their high energy efficiency and superior insulation.

Modular construction expert Tony Frost notes: “When you walk through such a building, it feels like you’re inside a massive concrete structure.”

People want to be more involved in decision-making.

“Alright,” you might say, “we can build anything we want — and pretty fast, if we choose to and find the right technologies. But what about people? Won’t they ruin it all?”

And you’d be right. If you fill a city of the future with people who still have the same old values and mindset, it won’t work. Jacque Fresco often said this when asked why his city was never built: “What’s the point if people stay the same?” Before building a new world, we must prepare those who will live in it.

That’s why I want to emphasize: the city of the future isn’t really about technology — it’s about people. Not about futuristic houses or innovative materials, but about the mindset and culture of those who inhabit them.

Many overlook an important detail: in an interview with Larry King, Fresco mentioned that in the future city, there would be no mayors or politicians — and that was intentional. He believed that management should be based not on authority but on knowledge; not on orders but on understanding and responsibility.

We must start thinking now about how new cities will be organized — how people will make decisions not through centralized power structures, but through new forms of collective participation that have already proven effective in experimental communities.

When people feel they truly influence the life of their city, they begin to care for it — and that’s what builds the foundation of a sustainable society.

Otherwise, new cities risk turning into the old ones: same people, same mistakes, same belief that “someone in a fancy office” will fix everything. And importantly — we don’t need to reinvent everything from scratch.

For example, starting in 1989, residents of Porto Alegre, Brazil, began deciding for themselves which projects should be funded by the city budget. This approach helped address the needs of poorer neighborhoods and significantly improved quality of life. In the first ten years, almost every household gained access to water and electricity, and the share of funding for healthcare and education grew several times over. The experiment was so successful that similar practices later spread to hundreds of cities worldwide.

In Paris, for instance, citizens have been deciding for several years how to spend about five percent of the city’s budget — hundreds of millions of euros. Residents propose projects, vote, and the city government is obligated to carry out the winning ideas. As a result, new parks, renovated schools, and support programs for people with disabilities have appeared across the city — the kind of initiatives that rarely get priority under traditional bureaucracy.

In Gdańsk, Poland, they went even further: if over 80% of participants vote in favor of a proposal, the authorities are legally required to implement it. This approach showed that civic participation doesn’t slow down city management — it makes it more effective: fewer protests, more trust, and shared responsibility.

Similarly, citizens’ assemblies in Ireland and the UK brought together randomly selected residents to discuss major social issues — from climate change to abortion laws. The results led to real reforms based on their recommendations. Many participants later said the process helped them better understand how society functions — and increased their trust in government.

These are just a few examples of people consciously taking responsibility for governing and improving their communities. The mindset itself is shifting — from “someone else will decide for us” to shared responsibility toward each other. And that, perhaps, is one of Jacque Fresco’s core messages.

We don’t live in a vacuum between home and work. Every building, every road, every person — all are parts of a single living organism called society. The more responsible its people are, the healthier and more resilient that organism becomes.

This doesn’t mean decision-making systems alone determine prosperity. But when combined with Fresco’s other principles — the scientific approach, technological rationality, and humanistic values — it becomes one of the essential foundations of the future he envisioned.

Is there any demand?

Even if the city of the future — as we’ve already established — can be made real both technically and socially, where advanced technologies go hand in hand with the civic responsibility of its residents, one question remains: will there be demand for it?

Not just the desire to “live in such a place” (which, I think, is obvious), but genuine interest from investors, foundations, and governments willing to fund such initiatives.

To be honest — it’s complicated. Don’t get me wrong: there’s no shortage of “cities of the future” in development today. Some exist only on paper, others are already under construction. But the real question is: are these truly cities of the future — or just modernized versions of the old ones, with the same problems dressed up in new packaging?

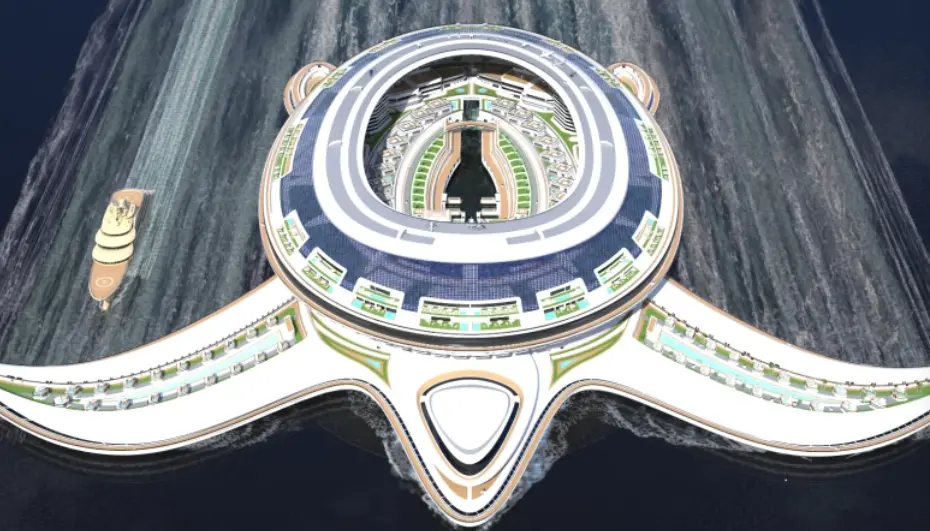

One of the most talked-about projects is Pangeos, a floating city concept shaped like a giant turtle. Its estimated cost is around 8 billion dollars, designed to house about 60,000 residents. But for now, the project faces major challenges — mainly lack of funding and the absence of supporting infrastructure. And while it’s an impressive and beautiful idea, in reality it remains more of an architectural dream than an actual city.

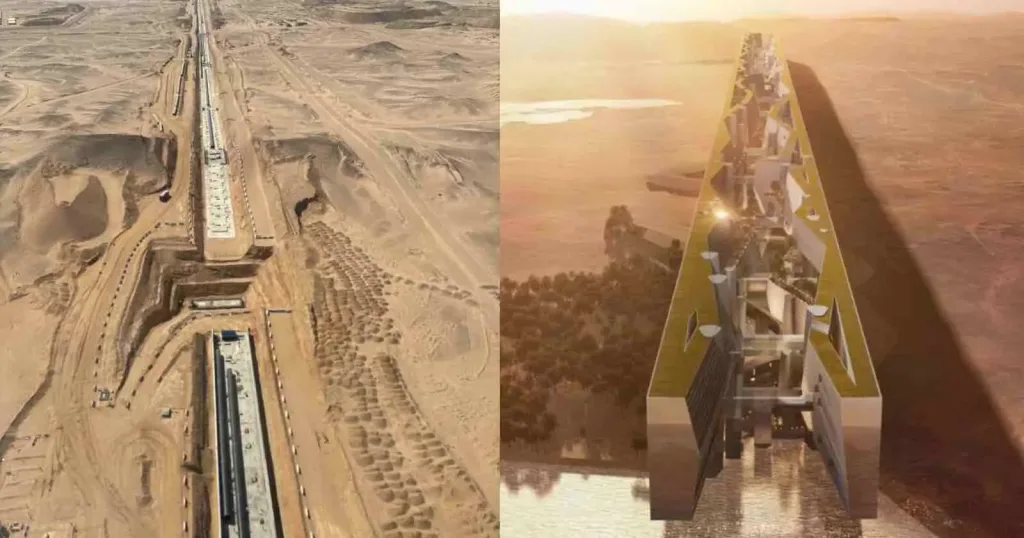

Another well-known project is The Line — a linear city that not only secured funding but is already under active construction in Saudi Arabia. It’s not going perfectly: some ideas had to be scaled down, deadlines were extended, and teams have changed multiple times. Still, construction continues, though not as fast as originally planned.

The concept envisions seamless logistics and full reliance on clean energy. Cars and roads are completely eliminated, with everything people need located within walking distance. Instead of traditional streets, there will be elevators and a vertical layout designed to save land and space.

As for citizen participation in governance — it’s a different story here. According to the developers’ plan, the system or artificial intelligence itself will analyze residents’ behavior and automatically adapt the urban environment to their needs.

In my opinion, there really is demand for something new. Modern cities — even with all their “adaptations” — no longer meet people’s needs. Companies and governments understand this and are trying to create new formats of urban life. However, despite massive budgets and resources, most of these projects are still built within the old economic model, where profit and prestige come first.

As a result, human values, awareness, and personal development often remain secondary. The focus is usually on technology and environmental impact — not on the human being at the center of it all.

Still, it’s encouraging that some projects are being funded not for profit, but for progress. Take the Large Hadron Collider, for example: it cost around three billion euros to build, and even now — despite not yet achieving all the expected results — it continues to be expanded, with even greater investment. Not for immediate gain, but for knowledge and the future.

Conclusion

So, is Jacque Fresco’s futuristic city actually possible? As we’ve already seen — yes, it can be built. There are no insurmountable technical or organizational barriers: all it takes is solid planning, a united team, and earned credibility.

However, to reach such a city, dreaming isn’t enough — we must act. Our movement has already come a long way and has grown far beyond a simple initiative. If we turn our dreams into concrete actions, the chances of realizing the future world Jacque Fresco spoke about will increase many times over.

That’s why I invite everyone who shares Jacque Fresco’s ideas to create their own projects based on the common concept and join existing teams.

Back in 2021, I took part in creating videos together with the team of the English-speaking YouTube channel The Venus Project. However, due to the leadership’s refusal to publish Jacque’s lectures for free, I started producing videos with the Extensional channel team, where I spent about two years as a producer, scriptwriter, and video editor, releasing an entire playlist on General Semantics and other topics. Currently, I have dedicated myself to working with the Earth Renovation team.